Perry Local Schools - Four New Elementary Schools

Driven by the goal to provide the best educational facilities for their young students, Perry Local Schools is in the midst of an ambitious task; the design and construction of four new elementary schools across the district. After passing a bond issue in early 2020, the district partnered with the Ohio Facilities Construction Commission and ThenDesign Architecture to fund and design these new buildings. Addressing the challenge of aging infrastructure in their current facilities, these new schools will provide a better organized school layout, community focused spaces, new technology, and a more comfortable and collaborative environment for students to learn in. Now well into the design process, each school showcases a unique characteristic of the Perry Massillon community, with the buildings slated to be completed by the fall of 2023.

While it has proven challenging to collaborate on a large-scale design process during a pandemic, the efforts of the Building Focus Group, along with many other community volunteers and educators has provided valuable insight to allow these new schools to serve Perry Local Schools for decades to come.

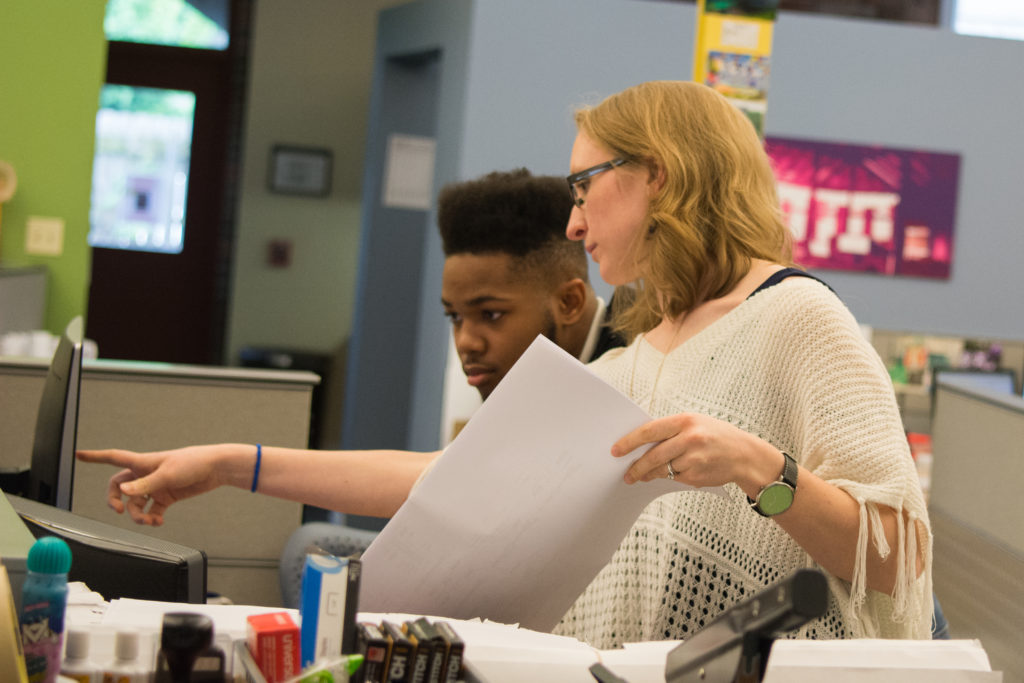

Students from Perry Local Schools speak about the impact good educational facilities can make on learning.

A Challenging Environment

The district currently has five elementary schools, (Genoa, Knapp, PJ Lohr, Watson and Whipple Elementary) each of which serves around 500 students and has been in the community for decades–most having been constructed in the late 1950’s and early 1960s. While well cared for, they are reaching the end of their lifecycle. Ongoing maintenance and repair costs for each building have begun to exceed the costs of new facilities. When this is paired with difficult accessibility for most of the buildings, inadequate parking and bus circulation space, along with dated air handling and electrical systems, it is clear new structures would better serve Perry students.

Additionally, as education has evolved over the decades, spaces within the original buildings became more fragmented and the historic layout of the existing schools no longer worked with the curriculum or met students’ needs. As an example, “special education” and student wellness within most elementary schools has become very important but in historic schools, there is usually very little space allocated for this crucial need.

The technological and organizational limitations of historic schools necessitated new buildings and presented the unique opportunity to reorganize educational spaces and create a modern educational environment for young students.

The Perry Local Schools: Building Focus Group

A tremendous amount of work went into the developing designs for the four new elementary buildings. To specifically tailor these buildings to suit educators, the district established a “Building Focus Group.” This special group was composed of principals, teachers, special education administrators and representatives from food services, music, and athletics across the four existing schools. This group of 25-30 members met weekly for almost 5 months, to discuss how the new buildings would function. Ryan Schmit, Project Manager for the project commented: “We would meet with the Building Focus Group for an hour or two and go through plan concepts, building feature concepts, talk through pros and cons and then afterwards issue a homework task each week.” He continues, “Each representative would take that assignment back to their groups, then send us additional information. We shaped the buildings according to educators needs. These groups really drove the design of the buildings.”

The involvement from the administration, educators and various community members ensured the design for each school was “staff driven” and was arranged to meet the educational scheme of the district.

The “Building Focus Group,” represented dozens of educators and hundreds of hours of shared design process that was crucial to each new facility.

Concept Imagery for the four new elementary schools:

Perry Local Schools - Concept Imagery for the four elementary schools in the district

Unique Identities in the Perry Community

Early in the design process, a “brainstorming committee” was tasked with identifying unique characteristics of the Perry community that could inform the elevations of the buildings. This committee was made of longtime residents, members of the historical society, young people, and alumni of Perry Local Schools. Through many meetings and long conversations, the group identified several qualities of the community which could be reflected in the overall exterior aesthetics of the buildings.

The team identifies four key characteristics. These included Perry’s strong rural and agricultural roots, the patriotic undercurrent in the community, their strong presence in the steel manufacturing industry and the district’s emphasis on performing arts and music in education. These qualities were woven into the architectural exterior of the four new elementary schools to showcase these unique qualities in the community.

- Lohr Elementary School – Borrowing aesthetics from rolling fields and the agricultural land that characterizes many acres in the Perry community, the building elevation employs a natural color scheme with masonry patterns on the brick face to replicate the waving fields of corn and wheat commonly found in the surrounding areas.

- Southway (Knapp) Elementary School – This school borrows the red brick patterns from historic and current local manufacturing plants, while also surfacing patterns of crisscrossing steel beams on the exterior.

- Whipple Elementary School – The façade of this school seeks to reflect American patriotism and a respect for the military through its use of colored masonry. It evokes feelings of pride, formal parades, and appreciation for the freedoms enjoyed in this country.

- Watson Elementary School – This school borrows from Perry’s musical tradition by employing contrasting light and dark masonry which evokes an image of musical stanzas to create a playful pattern across the school’s shared spaces.

While each building is unique in its exterior treatment, they share similar layouts, to unify user experience. The exterior patterns root the buildings in the community’s heritage and create a playful and colorful environment for elementary students.

New Educational Opportunities

A key design principle for all four schools was to be rooted in the community and allow them to be easily accessed for events and activities. These are “community buildings” and not only do the aesthetics of the exterior signal this, but the parking, entrance and shared spaces were carefully designed to help parents and guests easily navigate each school.

In the early stages of the project, superintendent Scott Beatty remarked: “We’ve learned relationships are important,” the superintendent said. “In smaller schools it is easier to build a relationship with a young person. You have to build interpersonal positive relationships with kids for them to learn and grow.” This led to the decision to ultimately construct four new buildings, within a variety of collaborative features to educate students.

The new schools are flexibly designed to accommodate both traditional education methods along with collaborative learning spaces. Special consideration was given to each building’s “shared spaces,” like the gymnasium and student dining. These can easily be used for a variety of large activities during the day with the gym serving as a large auditorium space. Each school’s media center (library) features special furniture that encourages collaborative group work and adjacent shared rooms where educators can teach outside their classrooms.

The new buildings incorporate better air handling and filtration systems, providing air conditioning and better indoor air quality overall. Daylight is also important and windows in the buildings create brighter and more open indoor spaces. Technology is better integrated throughout the buildings through additional electrical access in classrooms, upgraded internet connectivity and equipment access in the media center.

The project timeline for the completion of the four new elementary schools.

A Future Facing District

All four schools are in the “design development” phase, which is slated to be finished in the fall of 2021. As this phase is finished, the design team looks forward to releasing more detailed renderings of the facilities towards the end of the year. Construction is planned to start in early 2022, with all four buildings completed and occupied for the 2023-2024 school year.

To stay up to date on future construction announcements, visit the Perry Local Schools website.

Ryan Caswell

Communications

Get our newsletter with insights, events and tips.

Recent Posts:

ThenDesign Architecture Celebrated its 35th Anniversary

Capital Improvement Plans Work

Rocky River’s Transformative Renovation

Cuyahoga Falls 6-12 Campus Construction Tour

Claire Bank Selected as 40 Under 40 Honoree